Collateralized Mortgage Obligation (CMO)

What is a collateralized mortgage obligation?

A collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) refers to a type of mortgage-backed securities that contains a pool of mortgages and sells them as an investment. Organized by maturity and risk level, CMOs receive cash flows when borrowers repay mortgages as collateral for these securities. In turn, CMOs allocate principal and interest payments to their investors based on predetermined rules and agreements.

First issued by Salomon Brothers and First Boston in 1983, CMOs were complex and included many different mortgages. For many reasons, investors were more inclined to focus on the income streams offered by CMOs rather than the health of the mortgages themselves. As a result, many investors have purchased CMOs full of subprime mortgages, adjustable-rate mortgages, mortgages owned by borrowers whose income wasn’t verified during the application process, and other risky mortgages with a high risk of default.

The use of ECLs has been criticized as a provoking factor of the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Rising home prices made mortgages look like a safe investment, encouraging investors to buy CMOs and other MBSs. Still, market and economic conditions led to increased foreclosures and payment risks that financial models could not accurately predict. The effects of the global financial crisis have led to increased regulation of mortgage-backed securities. In December 2016, the SEC and FINRA introduced new rules that reduce the risk of these securities by setting margin requirements for covered agency transactions, including collateralized mortgage obligations.

Understanding collateralized mortgage obligations

Secured mortgage obligations consist of several tranches or groups of mortgages organized by their risk profiles. Tranches typically have varying principal balances, interest rates, maturities, and default rates and represent complex financial instruments. Secured mortgage obligations are sensitive to changes in interest rates and changes in economic conditions such as foreclosure rates, refinancing rates, and the rates at which real estate is sold. Each tranche has a different maturity date and size, and bonds are issued against it with a monthly coupon. The coupon provides monthly payments of principal and interest.

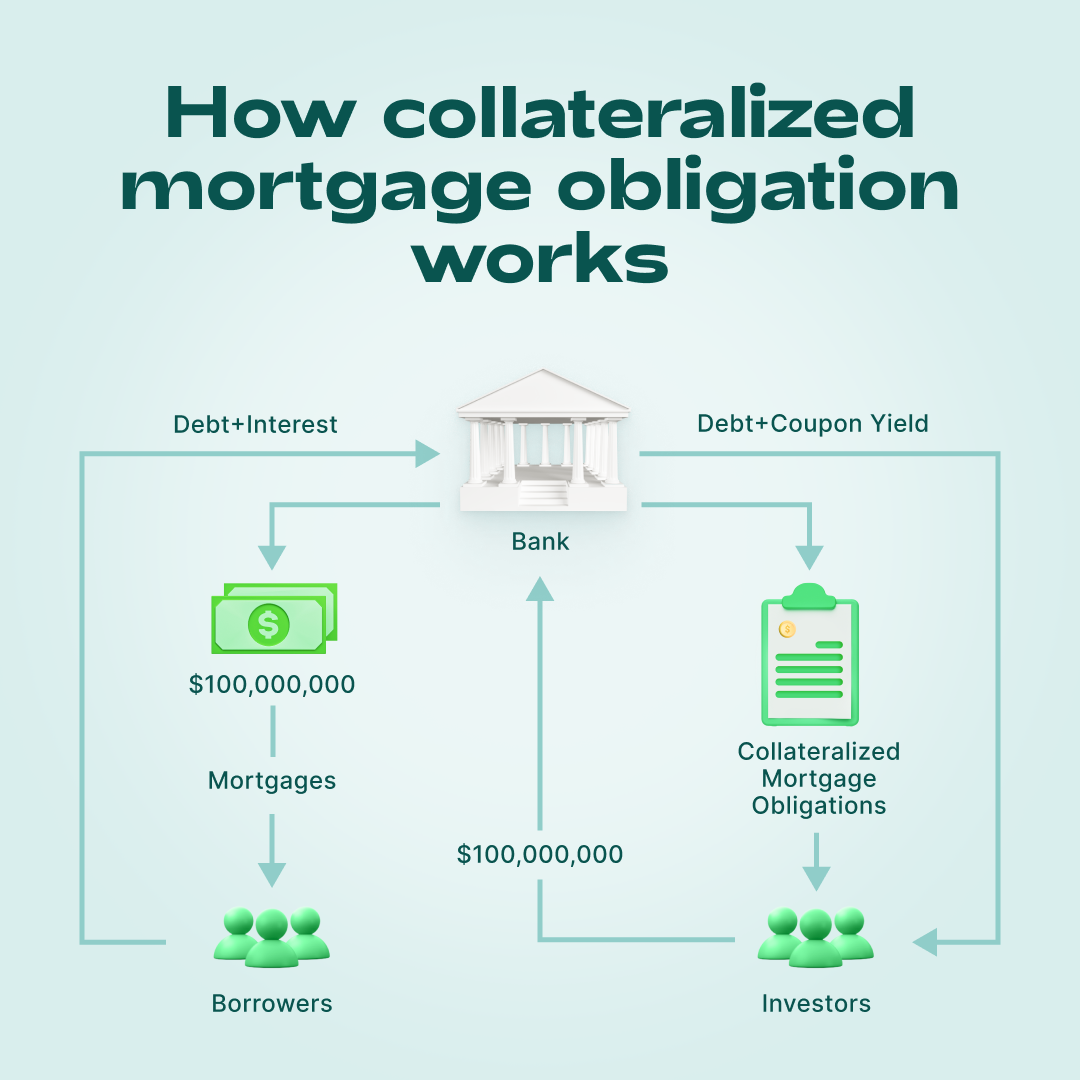

To illustrate, let’s look at the mechanism in the picture. Suppose a bank issued a mortgage loan for apartments in the amount of $100,000,000 and immediately issued CMOs for the same amount. The pool of bonds is put up for auction. Investors receive a long-term guaranteed income with potentially low risk by purchasing bonds. The bank uses the money received from investors to issue new loans. Part of the interest on the mortgage goes to the payment of coupon income, and the rest is the bank's profit.

CMO vs. CDO

Like CMOs, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) consist of a group of loans pooled together and sold as an investment vehicle. However, while CMOs only contain mortgages, CDOs have a range of loans such as auto loans, credit cards, commercial loans, and mortgages as well. Both CDOs and CMOs peaked in 2007, just before the global financial crisis, and their value plummeted after that. For example, at its peak in 2007, the CDO market was worth $1.3 trillion. For reference, in 2013 it already cost $850 million.

CMO vs. MBS

Mortgage-Backed Securities, or MBS, is any investment instrument containing a package of residential mortgages. Organizations that offer mortgage-backed securities buy these loans from banks or financial institutions.

When borrowers pay off their mortgages, MBS receives cash. Investors in MBS receive payments according to a certain schedule. The investors’ income is based on a percentage agreed between the investor and the MBS offering entity on interest and principal payments made on loans within the MBS.

A CMO is a type of MBS that differs from traditional MBSs in that mortgages in CMOs are divided into categories or tranches based on risk and maturities

The importance of risk level with CMO

When it comes to collateralized mortgage obligations, determining the risk level is critical.

Because CMOs are often grouped into tranches by risk, it is crucial to pay attention to them. Since CMOs are mortgage-linked, there are several reasons why some tranches are considered low-risk, such as the borrowers' credit rating or the amount of monthly debt they have.

Conversely, higher risk tranches will contain borrowers with higher credit, higher foreclosure rates and interest rates. The lower the risk, the more likely your money will be returned in total, although your payouts are likely to be lower. Again, it's all about what the investor is specifically looking for in an investment vehicle. Maybe an investor is willing to take risk if it means they can earn more in the short term.